UPDATE IN 29.09.2024

Brazil have around 33,379 spp. of described angiosperms, with over 18,000 endemics, showcasing an exceptional diversity of adaptation forms in soil, freshwater, coastal environments, and upon other plants. Here, we propose to classify the country's plant diversity into 50 categories of vegetative forms, based on extensive bibliographic research.

The vast majority of Brazil's angiosperm diversity fits into ordinary terrestrial forms of (1)tree, shrub, epiphytes, lianas, and herbs. Trees range from measly 2cm to 88m meters (Dinizia excelsa), exhibiting various patterns of branch architecture, leaves, barks, flowers (many cauliflorous, some flagelliflorous), and fruits; their leaves span from afilous species to Coccobola gigantifolia, with simple leaves reaching up to 3m in width. Similar patterns are observed with shrubs and herbs. Lianas, in turn, can be flexible, like in Cucurbitaceae and Convolvulaceae, and woody, like some Fabaceae. This category also includes a significant portion of terrestrial hemiparasites, as in Krameriaceae, Orobanchaceae, and Santalales.

Some variants of shrubs stand out: the (2)branching xilopodics, with underground organs, notable examples in Brazil like Anacardium, Jacaranda, and Stryphnodendron; the ultra rare (3)non-branching xilopodics, like Sinningia helioana, where leaves grow directly from the bulb; (4)caudiciforms, deriving from herbs but creating a woody base, like some Bulbostylis and many Cryptanthoids; (5)hyper-thorny, sometimes leafy, with extreme forms like Quiabentia, Colletia, and Discaria in Rhamnaceae; (6)cushions, sparsely represented in Brazil, with notable examples in Paepalanthus; (7)non-Cactaceae succulents, in Brazil represented by Portulaca, some Peperomia and Euphorbia; rare (8)spiny succulents non-Cactaceae, like Diosocorea basiclavicaulis; (9)ephedroid, sparsely represented in Brazil but identified in Polygonum, Orthosia, and some Spigelia; (10)dracenoid, with notable examples in Brazil being Vellozia and Cordyline; (11)ground rosettes, spiny or not, well represented in Brazil by many Bromeliaceae, Furcraea, Orectanthe, and Eryngium; (12)caulirosules, with the most notable example in Brazil being Prestelia and some Microlicia; and (13)phyllocladoids, like some Phyllanthus and Brasiliopuntia.

The most notable tree variants are the forms (14)cecropioids, well represented by Cecropia, and (15)mangrove species, which migrated to the partially saline environment on the coast, with representatives of Rhizophora, Conocarpus, Laguncularia, and Halairanthus in Brazil.

Some plants, between shrub and tree size, have assumed a (16)candelabriform non-cacti aspect, with leaves at the extreme branches, as seen in some Merianthera, Jatropha, some Caricaceae, Hyptis, Wunderlichia and Mimosa.

Among herbs, they can be as tiny as Lepuropetalum at 2cm in diameter to giants like Phenakospermum. Some creep in environments forming carpets, the (17)carpet-forming, like Raddiella, Micranthemum, Callisia, Elatine, and some Euphorbia and Pilea, some Convulvulaceae, Rubiaceae and Lycianthes. Others, in pre-marine environments, have assumed the (18)salicornioid habit, like Sarcocornia and Batis. Still near the sea, some have taken the (19)sesuvioid habit, like Sesuvium, Ammania, Rotala, Laurembergia, and some Gomphrena. Two other interesting categories of herbs are the (20)graminids, typical of Monocots like Tofieldiaceae, Juncaginaceae, Velloziaceae, Cyclanthaceae, Nartherciaceae, Typhaceae, Rapateaceae, Thurniaceae, Juncaceae, Cyperaceae, Poaceae, Eriocaulaceae, Xyridaceae, Commelinaceae, and Haemodoraceae; the (21)juncoid aphyllous, as seen in Glaziophyton mirabile; and the (22)bulb-bearing, like Amaryllidaceae, Asparagaceae, Orchidaceae, Iridaceae, and at least a single Pitcairnia.

(23)Giant herbs may include members of Araceae, Taccaceae, Orchidaceae, Worsleya, Eriocaulaceae, Heliconiaceae, Strelitziaceae, Maranthaceae, Cannaceae, Zingiberaceae, Costaceae, Gunneraceae, Alstroemeriaceae, and Caricaceae; whereas (24)sacciform-leaved herbs only include Saccifolium bandeirae from Mount Neblina.

Among epiphytes/lianescent, four myriad forms stand out: (24)aerial parasites, strongly represented in Loranthaceae and Santalaceae; (25)hoyoids, growing adherent to the substrate, where in Brazil some Peperomia, Constantia, Monstera, Acianthera, Marcgravia, and Codonanthe can be mentioned; (26)pendulous, like some Rhipsalidae, Dichaea and Isochilus; (27)electric-grid epiphytes, like Tillandsia recurvata; (28)negatively growing lithophytes, like Tillandsia reclinata; (29)cacti-epiphyllous, like Hatiora and many Rhipsalis; (30)strangulating, like some Ficus and Spirotheca; and (31)tank epiphytes, like many Bromeliaceae.

Some notable types include plants that encompass more than one major group, like the (32)bambusoids, which include herbaceous forms (in Orchidaceae and Marantaceae) and woody forms (like true bamboos), the (33)palmoids, including shrub-like forms like Cyclanthaceae and many Arecaceae, and tree-like forms, like most Arecaceae; and the (34)odd leaf forms forms, as ericoid, passerine, microphyllous, quandrangular or worled leaves at the stem, widely present in Brazilian savannas, found in members of Myrcia, Spermacoceae, Declueuxia, Mandevilla, Sauvagesia, Ruehssia, Minaria, Hyptis, Lychnophorinae, Lucilia, Baccharis, Agrianthus, Catolesia, Hypericum, Heteropterys, Turnera, some Linum, Moninna, Senega, Chamaecrista, Cuphea, Cambessedesia, Microlicia, Marcetia, Microtea, Caryophyllaceae, Xerosiphon, Froelichiella, Ledothamnus, Declieuxia, Deianira, Calolisianthus, and Barjonia.

All the above plants are essentially terrestrial and amphibious. Many forms are aquatic, notably the (35)floating, like Nympheaceae, Lemnoideae, Pistia, Alismataceae, Phyllanthus fluitans, Ludwigia sedoides, and Nymphoides; the (36)submerged/aerial, like Cabombaceae, freshwater Hydrocharitaceae, Potamogetonaceae, Mayacaceae, Eriocaulaceae, Pontederiaceae, Ceratophyllaceae, Ranunculus, Myriophyllum, Podostemaceae, Callitriche, Anamaria and Lilaeopsis; and the (37)sea grasses, in Hydrocharithaceae, Ruppiaceae, and Cymodoceaceae.

Cactaceae, with the exception of Pereskioideae, some forms in Opuntioideae, and epiphytic cacti, stand as separate types: (38)opuntioid, like Tacinga; (39)microglobular, like Frailea; (40)common cactoid, thin or thick, like Cereus and Facheroa; (41)macroglobular, like some Parodia, Melocactus, and Uebelmania; (42)branching, with very thin branches, like Harrisia and Arrojadoa; and (43)massive-diffuse, like some forms of Gymnocalycium.

Four carnivorous forms deserve mention as well: the (44)pitchers, like Heliamphora; the (45)droseroids, like Drosera; the (45)round subterranean-leaves, as in Philcoxia; and the (47)Lentibulariaceae, in the case of Utricularia and Genlisea.

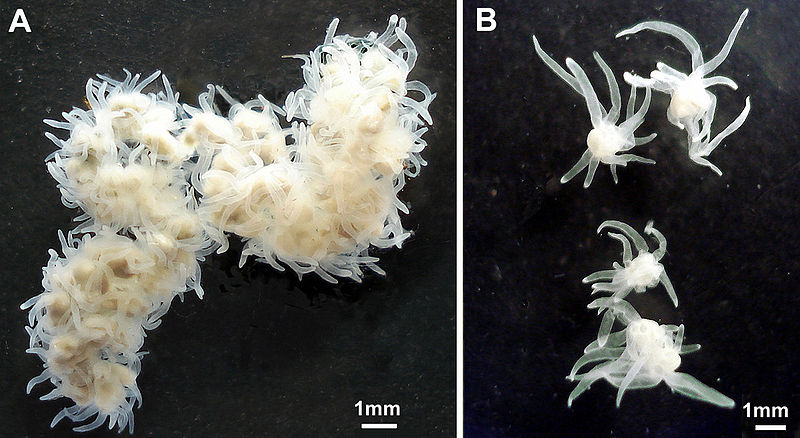

All the above plants are photosynthetic. There are three types of non-photosynthetic: the (48)achlorophyllous terrestrials, like Prosopanche, many Burmaniaceae, Thismiaceae, Triuridaceae, Orchidaceae, Balanophoraceae, Voyria and Voyriella; the (49)aerial lianas, like Cassytha and Cuscuta; and the (50)isophasics, like Apodanthaceae.